It was an honour and a real pleasure to join a panel at the Off the Shelf festival to discuss the recently republished novel The Good Lion. Fifty-odd tickets were sold and a few people who couldn’t make it asked if there was a recording. Unfortunately not – but hopefully this little write-up will make you want to buy the book.

The session was chaired by Professor Dave Forrest, who is currently working on the Wakefield writer David Storey and pointed out some interesting parallels in terms of Storey and Doherty’s shared love of sport and experience of mental health crises.

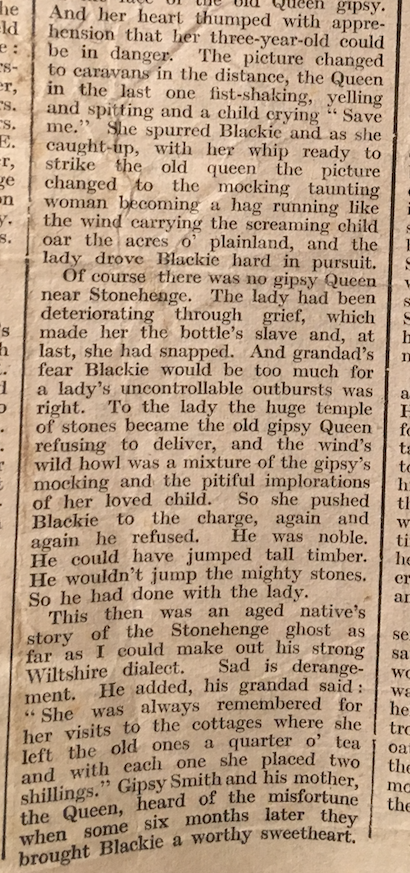

Steven Kay, an important Sheffield novelist in his own right (The Evergreen in Red and White is excellent) and an advocate for steel city literature through republication projects like this (and his 1889 Books blog), kicked us off with a short introduction to Len Doherty and his third, final and – in Steve’s view – finest novel. He talked about how his dad, a near contemporary of Doherty’s, had recommended the book to him and how he had immediately been struck by its understated genius.

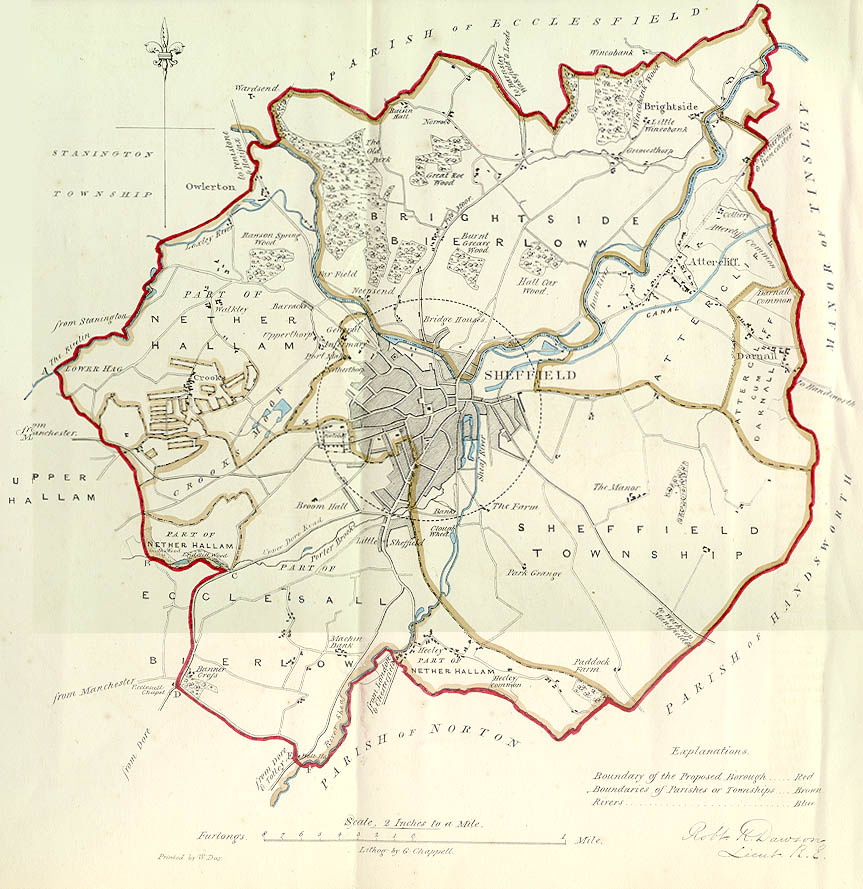

Steve read the evocative opening, which contextualises the action – and Sheffield itself – in the many-centuries-long development of metalworking in the area. He compared it to the opening of Adam Bede and lamented the fact that no contemporary publisher would consider a novel with such a slow opening.

Jack Chadwick, invited because he wrote a great piece about The Good Lion for The Tribune (paywall), read a section from a discussion between the novel’s central character, Walt, and a group of his roommate’s political and intellectual friends. It’s the first time Walt sets out his half-baked ‘Good Lion’ philosophy:

“Well, the scientist doesn’t see life as intellectuals and that kind do. He doesn’t care about morals and standards or ordinary good and bad. He thinks functional value and survival value are what count. So, to the biologist, the lion that kills a deer and eats it isn’t a bad lion; it’s a good lion.”

Jack then talked about the novel as a groundbreaking work of ‘autofiction’ published twenty years before the term itself was even coined. He drew useful comparisons with the work of Jack Hilton, whose Caliban Shrieks will be republished by Penguin next year (expect more on this – Jack has done incredible work to bring it back into print and I’ve posted here about it before).

My reading was from a conversation between Walt and his friend and on/off romantic interest, Elaine. I quote at length because part of the aim of the event was to give people a chance to appreciate some of Doherty’s writing, rather than just listening to us talk about it. They go to a jazz club together and Walt sneers at Elaine’s students friends:

‘Beards!’ he grunted disgustedly. ‘University types, I suppose…’

‘Don’t resent their being students, Walt. A lot come from poor families and it’s very hard for them.’

‘But I don’t resent them,’ he protested. ‘Why should I?’

University, he thought; years spent learning all kinds of things; an ingrained scholastic wisdom which would mean no doubts, no hesitation when more learned men talked, no sense of inadequacy when he read something which appealed to a knowledge simply not in his own mind… To have been at university must mean a huge confident power that made you equal to anyone in argument and conversation… Yet this had never occurred to him seriously before.

[…]

‘Just remember I’m a different kind. You’re not turning me into something out of a woman’s book.’ His accent was deliberately being increased. Incognizant anger was making him glower at her. ‘Your sort like to do that, don’t they?’

‘You’re trying to hurt, aren’t you? You nurse some kind of grudge against me, Walt – we shouldn’t go out together, really.’

[The argument escalates to the point that Elaine calls Walt a pig and he prepares to ‘ward off a slap’, recalling an earlier episode where his first girlfriend, Brenda, smacks him when he breaks off their courtship.]

He teetered back in the chair, determined to stare her out, but, as the staring lasted, asking himself why he gave way to these flashes of temper […] He was growing ashamed, and was slowly easing down the chair as her eyes suddenly filled. He was about to tell her not to cry when her small, rich mouth began curving and widening. She tilted back her head, her laughter tinkling out, then bent forward. ‘I can’t help it Walt; we’re just so ridiculous – glaring!’

‘We’re like kids, he muttered. Her eyes rose to his rueful look and she burst into fresh, helpless peals, with people glancing again at them. Her head bobbed, red and yellow light rioting over her tumbled hair, and Walt leaned over to tousle it with is right hand as he would have done with Bryan or another good friend. He trusted her suddenly. She looked up, her tanned face glowing, smile helplessly wide and eyes lambent with dark glee.

pp. 184-6

The passage is dense with themes from the novel and it would take more space than I have to unpack them all here. Walt feels guilt and shame often and acutely throughout the book, especially around his relationships with women. The reference to ‘a woman’s book’ here is self-referential: Walt blushes uncontrollably, especially early on, and the breathless treatment of romantic encounters and detailed descriptions of both men’s and women’s fashions could be straight out of a romantic novel of the era.

Part of Walt’s guilt and shame comes from the fact that his behaviour often reminds him – painfully – of his own abusive father. Walt inhabits a kind of toxic masculinity trap which Len Doherty does much more to examine than many (any?) of the ‘Angry Young Men’ of the period whose work has attracted much larger audiences and more critical attention. This argument culminates in a platonic trust and respect that complicates Walt and Elaine’s relationship. She challenges his sexism and homophobia and interrogates his ambivalence about sex itself, calling him a ‘Puritanical old wolf’. Elaine is Walt’s intellectual superior and she makes him reflect on his own identity and behaviour – and his snobbery and insecurity.

Which brings us to the issue of social class. Much of the literature of the post-war period is centrally concerned with the changing nature of class relations. The upwardly mobile grammar school boy is the archetypal writer – and hero – of much fiction of the period. But along with Alan Sillitoe, Doherty wasn’t a product of the grammar schools but a driven autodidact with an unshakeable commitment to writing. The social mobility that characterised the period and its literature is deeply problematic for Walt – as it was for Doherty. Walt is embarrassed by his mother’s aspirational attitudes and craves the solid class identity and noble working-class history that being a miner offers.

Doherty’s strong sense of class identity was expressed through his writing and his work as a miner but it was destabilised by the opportunities and friendships his success as a novelist brought. He spent time with Doris Lessing and her circle of friends in London, taking time away from the pit and the typewriter to mix with bohemian intellectuals (and Clancy Sigal, whose great book Weekend in Dinlock is a fictionalised account of his visits to Thurcroft to stay with Doherty). Although details of Doherty’s private life during this period are scarce, it’s hard not to see these dynamics play out through the relationships he so compellingly crafts between his characters in The Good Lion.

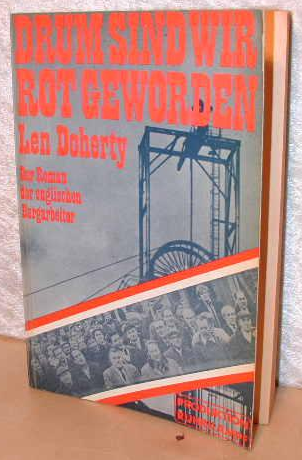

An hour was never going to be long enough to say everything – or even very much – about such a rich novel and such an intriguing writer. One thing that struck me that I didn’t get across, though, is the importance of the kind of ‘recovery’ work that led to this republication. The whole tradition of working-class writing is built on the dedication and hard work of people who care deeply about it: we wouldn’t have the unexpurgated version of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists if it weren’t for Fred Ball; nor would we have The Songs of Joseph Mather written down if it weren’t for the ‘hours stolen from [his] slumbers’ of the nineteenth-century cutler John Wilson. Steven Kay and Jack Chadwick have ensured thatThe Good Lion and Caliban Shrieks are restored to their rightful places in that great tradition – and that many more people will get to appreciate these excellent books.