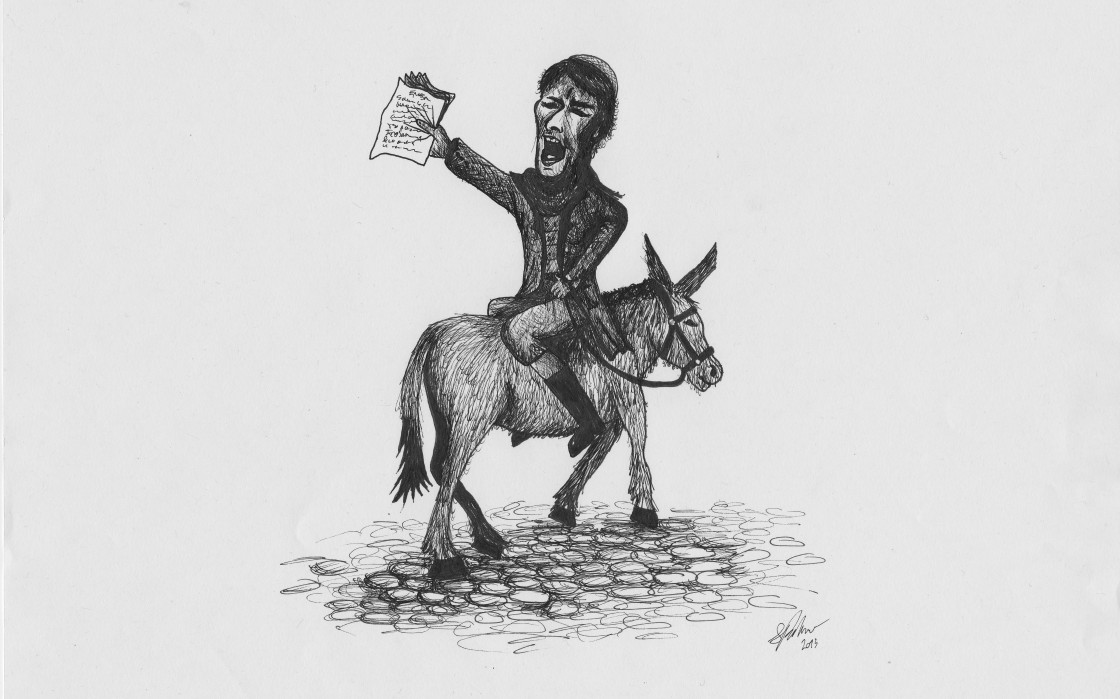

Thirty years after Mather died, the teenage son of a pen- and spring-knife maker was inspired, by a production of George Barnwell at the Theatre Royal in Tudor Street, to become an actor: he would become an eccentric local celebrity and another amazing Sheffield character who deserves to be more widely known. Harvey Teasdale started a spouting club* and staged illegal and often chaotic shows in pub back rooms, where it was not uncommon for unimpressed audiences to hiss and pelt performers off the stage. In the mid-1830s he was recruited to a travelling theatre in Retford and then to one at Conisborough: this show was such a flop that the actors had to steal potatoes and cabbages ‘to stifle the cravings of hunger’ that their ‘non-success had occasioned’.

Over the next fifteen years Teasdale performed in casinos, pubs and theatres as an actor, clown and skin performer**. Audiences on the northern circuit, and especially in Sheffield, were rowdy and sometimes violent and the players could be too: in Stockport the actor playing Hamlet picked a fight with Teasdale, who was playing the Gravedigger, and they came to blows in Ophelia’s grave (‘the source of great amusement to the audience’). After a run of shows at the Adelphi on Blonk Street in 1847, Teasdale staged an incredible publicity stunt for his benefit night:

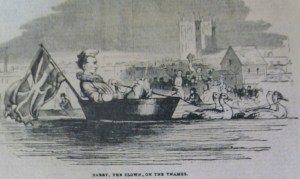

I hit upon a very novel expedient to draw a full house and it succeeded admirably. I advertised, in flaming placards, that I would sail down the river in a washing-tub pulled by ducks.

Teasdale tells us 70,000 turned out ‘to witness this marvellous and unprecedented sight’ shortly before admitting that a hundred people had died when a bridge gave way at Yarmouth during an identical caper not long before: in Sheffield, a wall collapsed in a yard on the Wicker and thirty people ended up in the river ‘with severe bruises’. Reports from the time suggest the ducks were ‘completely unmanageable’ and Teasdale ‘rolled and rocked about’ until he ‘got a good dousing’. Barry the Clown, pictured, was successful in 1840 on the Thames with geese, which are apparently much more trainable…

During this period Teasdale perfected the act for which he would become most famous: the ‘man monkey’. In Grantham he took this act to new heights in an event he describes with characteristic modesty:

It was in this theatre that the most daring feat that ever was performed in any theatre took place. The times were dull, the drama was getting stale, and it required something out of the common line to bring people into the theatre […] It was announced that the man monkey would make the daring and unparalleled leap from the gallery to the stage! […] I need hardly say it was a splendid and great financial success.

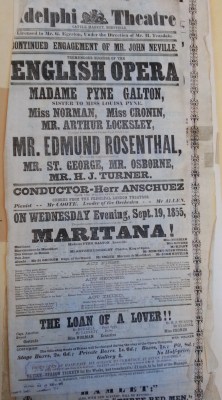

In Darlington people apparently asked if Teasdale was a real monkey, and along with his clown act – acclaimed in Cardiff but slated in London – he enjoyed a period of relative success, playing in Edinburgh and across the north and even undertaking stints as manager at several provincial theatres. This success elsewhere, combined with desperation on the Sheffield entertainment scene, which endured several poor seasons in the 1850s, led him to become manager of the Adelphi in 1855. This is one of his playbills:

The sheer variety of entertainment on offer is amazing: there are musical acts, Shakespeare plays, ‘low’ comedy and skin performers, crime and sensation dramas and pantomimes. Teasdale’s spell as manager wasn’t a great success, but it reveals him to be a committed and driven actor and manager who sought to provide Sheffield audiences with entertainment of every height of brow and opportunities to see many of the era’s biggest stars.

The life of a showman, though, was a precarious one full of temptation: Teasdale omits to mention in his wonderful – if perhaps slightly fantastical – autobiography that he was twice brought before the magistrates for neglect of family. He is more candid about his struggles with drink, calling the aptly named Clown’s Head, which he managed for a time, a ‘cauldron of insanity, vice and folly’ and admitting that he often performed ‘in a complete state of inebriation’ (he also managed The Three Tuns in Silver Street Head, which to this day remains Sheffield’s most triangular pub).

Teasdale’s nomadic lifestyle and his problems with drink and gambling took an immense toll on his marriage, bringing about the calamitous event that would see him sent to Wakefield Prison and eventually emerge as a zealous teetotaler. In August 1862 Teasdale arrived at a house where his estranged wife, Sarah, was staying. He begged her to take him back and when she refused fired a blank pistol at her, before attacking her with a razor and attempting to cut his own throat. Teasdale’s statement in court suggests he was paranoid and thought Sarah was ‘getting her living in the streets’ and bringing their daughters up to do the same. Surprised at the leniency of the jury, who found Teasdale guilty of the lesser charge of ‘unlawfully wounding’, the judge sentenced him to the longest possible term of two years hard labour.

This event forms the pivot between the ‘Dark Side’ of Teasdale’s autobiography and the ‘Light Side’, which sees him convert in jail and join the Hallelujah Band (a forerunner of the Salvation Army) on his release. At a widely publicised event at the Temperance Hall in 1865, Teasdale burnt his costumes – including his monkey suit – along with scripts, scores and props. There were accusations that Teasdale had already burnt his costumes elsewhere, but he stuck to his new calling: he listed his profession as ‘lecturer’ in the 1871 census and advertised his services in the back of his book, The Life and Adventures of Harvey Teasdale, the Converted Clown and Man Monkey, which had apparently sold 42,000 copies by 1881.

Kathleen Barker, historian of provincial theatre, argues that Teasdale’s life has much to tell us about the history of entertainment in the nineteenth century. It is a unique insight into ‘the twilight shows of provincial city pubs of the 1830s: not quite gaffs, not yet casinos; and [into] the travelling booths still criss-crossing the country’ and ‘his career as a performer illustrates particularly well the interrelationship between the various genres of entertainment in that period. Teasdale could move from Shakespeare to pantomime to circus to music hall, without an eyebrow being raised at such versatility and breach of type-casting’.^ Teasdale’s is a remarkable Sheffield life that grants us an insight into the working-class culture of the mid-nineteenth century and the rise of temperance in the 1860s. His brilliant autobiography is a rare document of the seedier side of the entertainment scene in Sheffield and a moving account of an ambitious and driven performer who dusted himself down after every failure and bad review – and there were many – to try his hand at something new and put on a show for the public who he tirelessly tried to please.

* ‘A meeting of apprentices and mechanics to rehearse different characters in plays’, according to the 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue.

** An actor in full costume, like whoever was Chewbacca in Star Wars…

^ Barker’s papers at the Bristol University Theatre Collection, in which there are several files pertaining to Sheffield’s theatre scene, include a short, unpublished essay, ‘Spanning the Entertainment Scene – Harvey Teasdale, Clown of Theatre, Circus and Music Hall’.