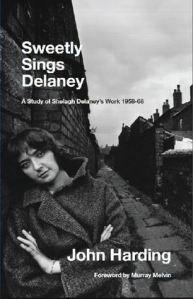

This is an overdue review of a book published almost a year ago. John Harding’s Sweetly Sings Delaney: A Study of Shelagh Delaney’s Work 1958-68 is a valuable exploration of the first ten years of a fascinating career. Jeanette Winterson wrote that reviews of Delaney’s first two plays ‘read like a depressing essay in sexism’ and called her ‘the first working-class woman playwright’. Such an important figure in the development of working-class writing deserves far greater critical attention than Delaney has received, and this book is a welcome step in the right direction.

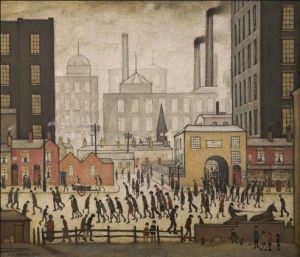

Since its publication, Salford City Council organised the first Shelagh Delaney Day on what would have been her 76th birthday (25 November 2014).* Given the then Director of Education’s public hostility to her depiction of Salford in 1958, Delaney might have found her officially sanctioned local hero status amusing. But this recognition rightly places her alongside Salford’s most famous artist, LS Lowry. The painter was a major influence on Delanay: his Coming from the Mill hung in her classroom and she gazed at it when her attention strayed from lessons (‘which was often enough’).

In LS Lowry is the very essence of a child … The universal truth – this loneliness of mankind – this loneliness is something we have always suspected at some time and Lowry has caught it – comic, cruel, beautiful, ugly and tragic.

Those last five words could equally describe the genius of A Taste of Honey. Just as Lowry had been a significant figure in representations of the industrial north a generation before, Delaney was a leading light in the rapidly changing cultural landscape of the 1950s. John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger – received at the time and seen since as a pivotal moment in post-war theatre – was made to seem tame and dated when A Taste of Honey swaggered out in front of an unsuspecting audience two years later in 1958. Apart from a too-detailed summary of the play (similar accounts of later works are understandable given their relative obscurity), the seventy-or-so pages Harding dedicates to its genesis, development, production and reception are by far the most thoroughgoing account yet offered of Delaney’s masterpiece. Harding notes that there are few extended analyses of the play (a chunk of my PhD thesis takes issue with Arthur Oberg and Edward Esche’s readings, the two most detailed academic engagements with it) and his seven short chapters are a useful antidote to this critical neglect.

On the first page we’re told that on her birth certificate her name is spelled ‘Sheila’ and that ‘why she changed it isn’t known’. Harding assumes it was to emphasise her Irish roots – of which she was doubtlessly proud – but skips over its wider significance. ‘Shelagh’ seems part of a concerted effort to cultivate the cult outsider recognisability of a JD Salinger or Françoise Sagan (with whom comparisons were made at the time). Delaney projected an image of herself as a bolshy, defiant and mysterious young woman intent on rocking the theatrical boat and shaking post-war culture out of its complacent conservatism.** Harding’s assumption is of no great significance but it is indicative of the book’s un-academic tone.

The advantage of this approach is the ready readability of Harding’s prose, which is pitched at the general reader as well as a more scholarly audience. He has amassed a great deal of material, much of it entertaining as well as insightful, and he stitches many and varied quotations into a coherent and compelling account of Delaney’s early career. Harding illustrates well how Delaney was, like many writers, an inveterate self-mythologiser, telling Joan Littlewood in the letter that accompanied the manuscript of A Taste of Honey that two weeks previously she ‘didn’t know the theatre existed’ and leading journalists to believe that she cut her cultural teeth in the music hall and on thrice-weekly visits to the cinema. In fact, she’d worked as an usher and regularly went to plays with her friend, the artist Harold Riley, who was ‘struck at the time by the extent of Delaney’s knowledge of the history of the theatre’.

Fascinating insights such as this, gleaned from interviews and an impressive range of sources, make Sweetly Sings Delaney an invaluable account of her early writing career. Harding sets out to show that Delaney ‘played an important role in both stage and film writing and that her contribution to the careers of film directors such as Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson was a significant one’. He certainly succeeds, and at the same time offers a comprehensive account of her early development and her relationship with Salford. For anyone interested in the first working-class woman playwright, it’s a must-read.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Shelagh Delaney’s Salford has great footage of the playwright in her home town.

*There’s a promotional video – with a very odd choice of backing music – here.

**This was surely part of what fascinated Morrissey about her: The Smiths used one of Arnold Newman’s portraits for the cover of Louder Than Bombs and Morrissey said ‘at least fifty per cent of the reason for my writing can be blamed on Shelagh Delaney’.