On Monday the 8th of September I sent this article – Tommy Youdan: Music Hall Hero – into Now Then (a great, beautifully produced free Sheffield magazine that’s had the good taste to publish a few of my articles in the past). The following day, on route to The Tumble near Abergavenny to see Sir Bradley Wiggins and the Tour of Britain, I got a call from Point Blank Theatre asking me to be… Tommy Youdan in a production about Harvey Teasdale at the Spiegeltent in Barker’s Pool for the Festival of the Mind. I ended up leading the Tour of Britain briefly over a famous road climb later on, so it was a pretty surreal day all-round.* This post is a slightly longer version of that Now Then article and I will post shortly about how and why I ended up being Tommy on stage and my experience of researching, devising and performing in the piece.

In 1844, Engels wrote that ‘immorality among young people in Sheffield seems to be more prevalent than anywhere else’. In fact, early music-hall was transforming working-class culture in Sheffield by introducing a huge variety of popular and ‘high-brow’ entertainment to affordable venues. One of the key figures in its development was the tenth son of a farm labourer from Kirk Sandal, near Doncaster. Tommy Youdan was born in 1816 and followed older brothers to Sheffield to look for work. After being a labourer, a silver stamper and a beerhouse keeper, in March 1849 he opened Youdan’s Royal Casino at 66 West Bar: it was so successful that it was enlarged twice that year to hold 1,200 punters and a stage big enough for elaborate shows. Despite its size and nightly entertainment admission was still free, suggesting drink was the main attraction.

But Youdan had grand plans and wanted to offer high quality, affordable entertainment to his working-class clientele. The 1843 Theatres Act required licences for all sorts of dramatic performances, and theatre managers were on the look-out for infringements so they could inform on music-hall owners who were encroaching on their turf. Youdan used phrases like ‘illustrated ballad’ and ‘duologue’ to describe operas and plays so he could offer a wide range of entertainments without a licence. It didn’t always work: in 1850 he was fined £20 for eighteen nights of ‘operatic performances’. The fact that Youdan could pay the fines shows that the working-class appetite for music and drama made it a lucrative business.

In the same year he changed the name to the Surrey Music Hall, a bold statement of intent because Sheffield’s foremost respectable concert room was the Music Hall in Surrey Street. The range of entertainment on offer was huge, from high-grade musicians, opera and ballet to animal acts, comics, ventriloquists, dramatic readings and ceiling walkers. Youdan’s blend of low prices, classy surroundings and programmes mixing high-brow and popular entertainment was so successful that it spawned a rash of copycat venues. When a rival took over a massive former circus in Blonk Street, opening it in 1851 as the Adelphi, Youdan responded by investing £5,000 on expanding to a capacity of 3,000. At Christmas 1851 he advertised his ‘ELEGANT ESTABLISHMENT’ as ‘the EMPORIUM OF ECONOMICAL INTELLECTUAL AMUSEMENT’.

The Adelphi got a theatre licence in 1852 and its manager and the Theatre Royal’s owners repeatedly took Youdan to court for staging unlicenced shows. Determined to prove his respectability, Youdan made himself a popular public figure through charity work and canny PR. He gave beef and blankets to the poor, hosted an open-air tea for 2,000 old ladies to celebrate the end of the Crimean War, offered train tickets to London and trips to the St Leger festival as prizes to his customers, leant his house band for public events and bought a menagerie of stuffed animals for educational display. But even his philanthropy got Youdan into trouble: in 1856 he advertised the sale of a 4-ton ‘Monster Twelfth Cake’ in portions, some containing medals entitling the holder to a cash prize. Cautioned by the authorities under the Lottery Act, he was forced to sell off the soggy, undercooked cake with no prizes.

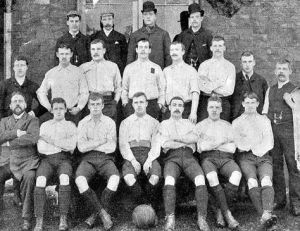

The only surviving photo of Youdan, centre in top hat, with his company after the fire.

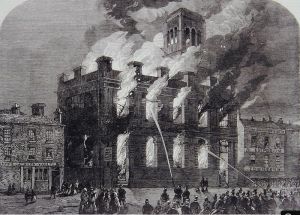

In 1858 Youdan’s popularity and public spirit got him elected as a Town Councillor and a member of the Board of Workhouse Guardians, positions in which he worked conscientiously to improve conditions for the Sheffield poor. The following year he took on the lease of the Adelphi, removing a major competitor, and used it as a warehouse. This turned out to be his saviour when, in 1865, the Surrey Music Hall burnt down. He reopened the Adelphi as the Alexandra New Music Hall and eventually got his theatrical licence, allowing him to bring the greatest stars of the day to Sheffield audiences at affordable prices.

The Burning of the Surrey Theatre, 1865

Not only did Youdan revolutionise music-hall, he also had a hand in the early development of the next great mass entertainment, football. He donated the trophy and prize money for the Youdan Cup, the first ever cup competition, featuring twelve teams from the Sheffield area including Pitsmoor, Broomhall, Heeley, Norton and the winners – and only team still going – Hallam FC (who still have it now). Even though he had retired in 1874 and died two years later – leaving £25,000 to his niece – The Alexandra was popularly referred to as Tommy’s right up until its demolition in 1914. Because of Youdan’s vision, drive and ambition, Sheffield had a much richer music hall culture than most other industrial cities. His love of popular entertainment and his desire to improve the lot of the city’s poor led him to have an important hand in the development of music and football in the city, two passions that its residents still hold dear.

The Youdan Cup presented to Hallam FC in 1867

* MOTORBIKE COP: You’re gonna have to pull over, there’s a race coming through

ME: I know, I’m winning!

MOTORBIKE COP pulls unimpressed face, speeds off.